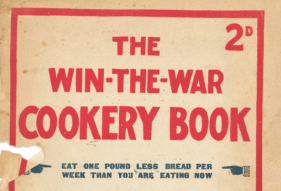

Cooking using a WW1 recipe book

In 2010 we came into the possession of a bruised and battered cookery book of genuine historical interest. You can see the whole book on our Pinterest page, here.

Published for the First World War’s Food Economy Campaign with the approval of The Ministry of Food, The Win-The-War Cookery Book from 1918 contains messages and recipes designed to encourage people at home to save bread and ration food to bolster the war effort.

As the British soldiers of the First World War fought on valiantly, The Win-the-War Cookery Book played a vital role on the home front with its waste-reducing advice through revised versions of traditional recipes.

To get a flavour of life back then, Great Food blogger Beth Wilmshurst decided to produce four WWI recipes from the book. She says: “I spotted some fairly alien ingredients amongst the recipes, such as cow heel, maize meal, and dripping, so it was time to dig out my hair net and start scouring the pantry…”

THE RECIPES

By Beth Wilmshurst

#1 Fish Sausages

I wasn’t initially enticed by the name of this dish, this being the first of my attempts to recreate a WWI meal. Though a fish-lover I am, surely a fish and a sausage should never cross paths. Then I thought about this concept a little more, perused the recipe, and decided that if a fish finger and a fish cake were to marry, this would inevitably be the product.

Of course, one must remember to be forgiving of dubious titles and unusual ingredients; rationing leaves little space for conventional cooking. This one, however, was one of the friendlier looking ones in the weathered pamphlet of WWI cuisine, so recipe at hand (or rather, in PDF), I donned my imaginary Edwardian apron and got to work.

The first on the list of ingredients: Two teacupfuls of cooked fish.

I admit it, I spent more than a few minutes deliberating what constitutes a teacup, and concerned myself deeply with the conundrum of how much fish I should attempt to squish into said cup. Eventually coming to the conclusion that guesswork was a much happier approach, I overcame the measurement hurdle and the rest followed pretty simply.

The outcome was definitely edible, and quite tasty. I was pleased and with the golden breadcrumb exterior, and positively beaming at the well-seasoned haddock interior. The sausage shape was not so easy to achieve. Sporting more of a potato croquette look, mine were short and stumpy. I’m sure a dollop of ketchup should help disguise that, unless I’ve exceeded my rations…

#2 Barley Bread

I am a bread-making virgin. Despite the self-professed baking-fanatic that I am, this is the shameful truth. So as if to scold myself for the neglect of such a timeless necessity, I am returning to the old traditions of bread-making – well, as old as the WWI era. I take to the kitchen, armed once again with the trusty Win-the-War Cookbook in the hope of a courageous bread victory. My opponent: Barley Bread.

The initial obstacle in this challenge was where on earth to locate the barley flour. Surely, I thought, this hasn’t served as an ingredient since 1918? Though proved wrong when I finally discovered one lonely bag on the shelf of an organic food shop, its packaging certainly led me to believe it had been sitting there on its dusty bottom since WWI.

Back to the kitchen, and a few battles awaited me.

Gills. Previously thought to be part of a fish’s anatomical makeup, are presented here on the recipe as a measurement. I was baffled, but managed to find out that one gill equates ¼ pint and added the ‘three gills of tepid water’ accordingly.

The other significant hurdle was kneading my dough. I wasn’t instructed as to how long to do this, simply that I should do it ‘well’. My patience clearly needs some exercising, as this part of the process was perhaps where I fell short. I think I was missing the vital air pockets that produce a light, fluffy loaf.

So was it a victorious attempt? Well, the overall finish admittedly produced a golden, rustic (brick-like) exterior. The centre on the other hand, was not so triumphant: fairly dense and a little stodgy. Perhaps it’ll make a nice bread & butter pud…or a nuclear bomb shelter.

#3 Parkin

There is no doubt that the women on the home front certainly had cooking nailed. Working my way through these WWI recipe challenges, I’ve learnt that the speculative nature of the processes involved mean much intuition is required.

This week’s challenge is no different, with the usual absence in the recipe of exact timings and common units of measurement. Hmm…wish me luck.

Having experimented with a hot savoury dish and tried my hand at baking bread, I decided to go for a sweet treat this time: Parkin. Whilst conducting a little research, I gleefully discovered my timing couldn’t be better. Traditionally, Parkin is made and devoured on or around Bonfire Night in the English North.

There are actually a few versions of this treacley snack – some are more cake-like, whereas the original Yorkshire Parkin is nearer the biscuit end of the spectrum. My attempt seems to be of the latter variety (well, as close as I could get it).

Like the teacup mystery of the Fish Sausages (see below), I had to take time to contemplate the sizing of a breakfastcup. I don’t think I ever really sussed this out, but nonetheless, in went a portion of coarse oatmeal. A teaspoon of ginger followed (I can do teaspoons), then a touch of salt. I added the margarine as instructed, and the treacle in its tablespoonfuls, but my heart sank when I saw “A little milk” in the recipe. I decided to pour the milk for the amount of time it takes to say “A little milk”, and this may have been unwise. The mix was sloppy when it was supposed to be a “firm paste”. The only solution was to contribute more oats, and this seemed to do the trick.

Formed into biscuit shapes and popped into the oven, I had no idea how hot or how long to bake them for. I settled for 150 degrees until golden brown (about 45 minutes). The outcome was a thick, gingery, crumbly biscuit, which actually tasted quite good. The added oats killed the sweetness a little… but I guess that makes for a more guilt-free treat. Now just a flask of tea, gloves, a woolly hat and a bracing walk among fallen leaves, and I’m all set.

#4 Surrey Stew

Delving for possibly the last time into this relic of food heritage, I take my culinary adventure through the Win-the-War Cookery Book south – Surrey Stew, to be precise.

Trying to dig up the roots to this casserole dish, I failed to find any snippet of evidence to explain its birth. The only thing to assume is that some hungry soul in Surrey made a casserole one day, added a personal twist (the cloves, perhaps?) and dubbed it a hometown classic.

Unlike my previous WWI creations, I did not struggle to translate measurements, or grapple with the time conundrum. I’m all too familiar with the process in a humble casserole. My main challenge in fact, was resisting the urge to add a bottle of ale to the mix. Fortunately I remembered the luxurious nature of such an element, felt a torrent of shame take me, and focused my efforts back onto this wholesome meal of rationed ingredients.

The first part of the recipe involved browning the pieces of beef in butter, having coated them thoroughly in well-seasoned flour (not wheat – so I chose barley). I was a little worried and reluctant – when making my beef-in-beer stew, I tend to just chuck the meat straight in, pink and mooing, and let the slow cooking do the job. I persisted with the instructions however, adding the onions, carrots, turnip, spice and herbs, seasoned well and popped into the oven for a few hours.

Victory. A delightfully tender and delicious stew emerged from the oven and warmed all its devourers from head to toe. “But no stock?!” they gasped, “No garlic?!” they exclaimed. Indeed, it was a surprisingly flavoursome dish (though I won’t be giving up the missing elements any time soon), and a classic wintery finale to my WWI journey.

For more blogs from Beth, click here